“You have to move inside” he said. Italian. Possibly. “Why?” I asked, abruptly. “Because the sign on the wall says you must” he replied. I laughed loudly. I’d been sat quietly, catching up on a few e-mails, in the courtyard of a hostel I’d found in the capital. By now dark, just the glow of my netbook screen to reveal my presence. Didn’t think that was disturbing anything. No more than the opera in a large marquee nearby. Wearily, and slowly, I gathered my belongings together and wandered off.

Despite the unwarranted interruption, the hostel was pleasant enough. Reminded me of the small workers hotels in Kazakhstan normally run by ethnic Russian women. Basic but always clean. No cockroaches. But where they differed is cost. Mine wasn’t cheap, just the least expensive option I could find. And simple things you’d often find included, towels or even wireless internet, would increase the cost by almost half. Not the most expensive city I’d visited, certainly not Baku in Azerbaijan with its eye watering prices, but still tough on the budget.

I’d travelled into the city a few hours earlier, a little jaded by the journey from Almaty, but not sufficiently tired to sleep. The train almost empty, the streets, the metro system quieter than I’d expected. Flags draped from windows, mostly as we’d passed through the suburbs. Nationalistic celebration? Perhaps. But a subdued atmosphere, as if in defeat.

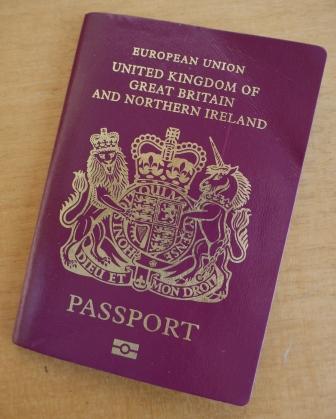

A third country where I hoped to be able to secure fresh visas sufficient to cross uninterrupted across China, and return to Kazakhstan. And a few other things besides. With little realistic prospect of securing a workable Chinese visa before my Kazakhstan one expired, I’d had to travel further afield. Nevertheless, elements of the Stans I thought. Plentiful parks and green spaces reminded me of Bishkek a few weeks earlier. And the man’s insistence last night on rigid adherence to rules, without proper explanation? Shades of the old Soviet Union?